A newly discovered chemical could help to treat cholera and other diarrhoeas. The compound may also aid the search for drugs to treat cystic fibrosis.

The chemical stops cells losing their fluids. In secretory diarrhoeas, the body pumps water into the intestine. In developing countries, dehydration caused by diarrhoea kills more than a million people each year.

Cystic fibrosis sufferers face the opposite problem - too little secretion in the lungs, resulting in an ultimately deadly build-up of mucus. This hereditary disease affects about 30,000 people in the United States.

A protein called CFTR controls secretion in both diseases. Researchers have now found a chemical that stops it working 1.

"We knew cystic fibrosis mice [lacking CFTR] don't get cholera," says biophysicist Alan Verkman of the University of California, San Francisco. "We thought that if we could block CFTR, we could limit secretory diarrhoea."

Verkman and his colleagues tested 50,000 molecules for their ability to stop CFTR working. They used human cell cultures, and a yellow fluorescent dye that shows up secretion.

One compound reversibly blocked CFTR, was non-toxic to human cells and mice, and reduced diarrhoea in mice with cholera by 90%.

The compound is a good candidate for treating cholera and other bacterial infections, such as traveller's diarrhoea. "The possibility that this could be used to treat disease is fairly substantial," says cell biologist Qais Al-Awqati of Columbia University in New York.

Oral rehydration therapy can treat diarrhoea. A salt and glucose solution stimulates the intestine to absorb water. But new treatments could help to prevent severe dehydration and death in the young and old.

Mirror-image diseases

Cystic fibrosis patients lack CFTR. "Secretory diarrhoea is like the opposite of cystic fibrosis," says Al-Awqati.

Verkman's discovery could aid the search for a cystic fibrosis drug to activate or replace CFTR. The CFTR-blocker could mimic the disease in pigs or rabbits, which have lungs that are similar to those of humans.

"Mice don't truly reflect cystic fibrosis," says biochemist Robert Beall, president of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation in Bethesda, Maryland. "We need an appropriate model with human-like symptoms to screen drugs."

References

Ma, T. et al. Thiazolidinone CFTR inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening blocks cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. J. Clin. Invest. ,110, 1651 -1658 , (2002). HOMEPAGE

KENDALL POWELL

Ultimi Articoli

Neve in pianura tra venerdì 23 e domenica 25 gennaio — cosa è realmente atteso al Nord Italia

Se ne va Valentino, l'ultimo imperatore della moda mondiale

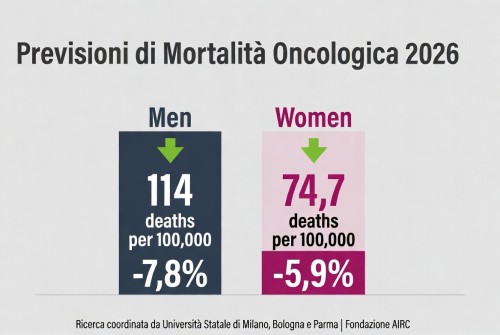

La mortalità per cancro cala in Europa – tassi in diminuzione nel 2026, ma persistono disparità

Carofiglio porta — Elogio dell'ignoranza e dell'errore — al Teatro Manzoni

Teatro per tutta la famiglia: “Inside and Out of Me 2” tra ironia e interazione

Dogliani celebra quindici anni di Festival della TV con “Dialoghi Coraggiosi”

Sesto San Giovanni — 180 milioni dalla Regione per l’ospedale che rafforza la Città della Salute

Triennale Milano — Una settimana di libri, musica, danza e arti sonore dal 20 al 25 gennaio

A febbraio la corsa alle iscrizioni nidi – Milano apre il portale per 2026/2027